Out of sight out of mind: marine mine waste disposal in Papua New Guinea

Waste-in the sea

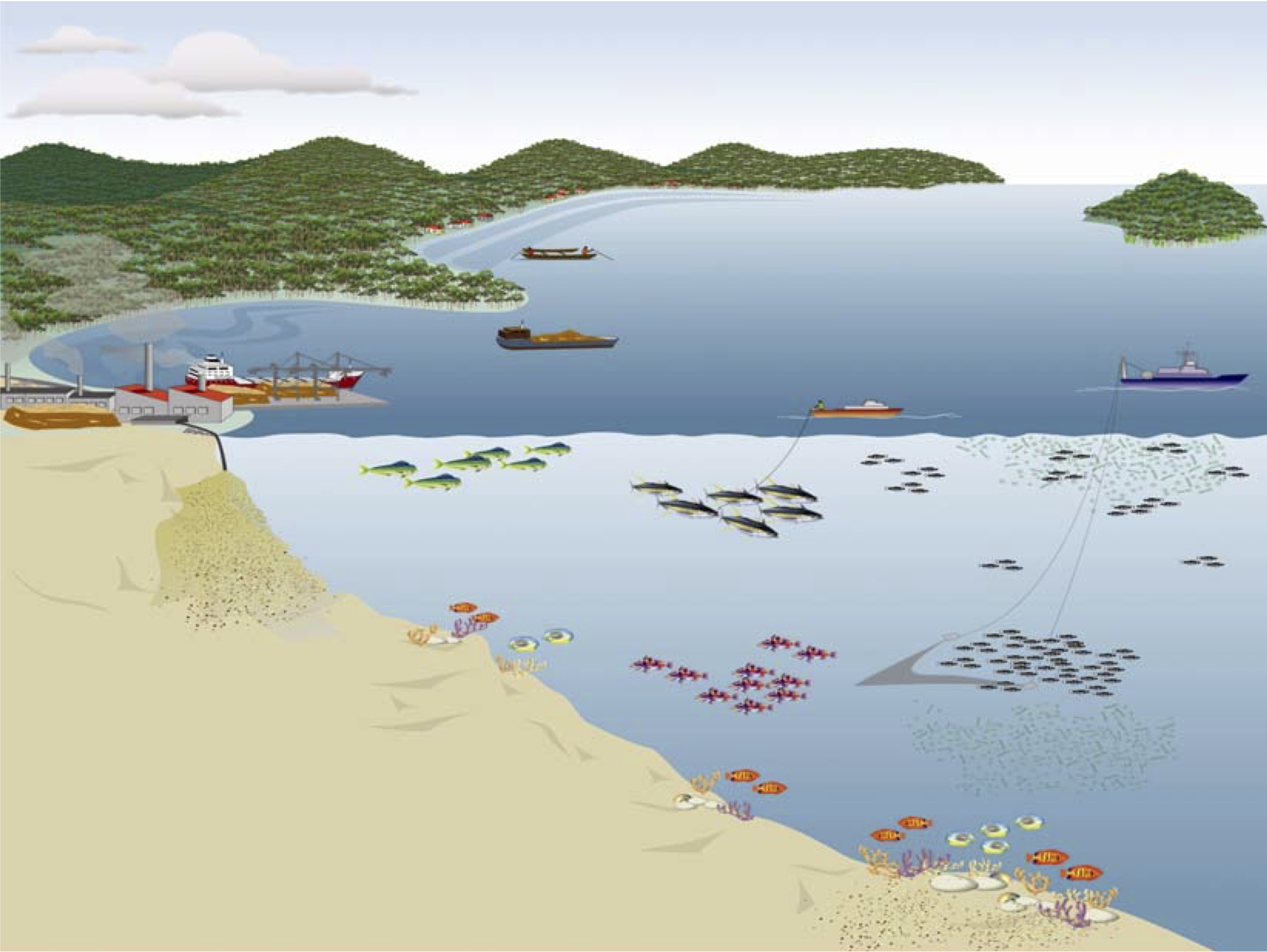

Papua New Guinea (PNG) could be said to be a world leader in Deep Sea Tailings Placement (DSTP). DSTP involves discharging of finely ground rock, chemical reagents and water used in the mineral extraction process directly into the ocean and has been carried out since the 1970s. Currently it is used only in PNG, the Philippines, Indonesia and on the Turkish Black Sea. Contrary to what the term implies, however, the tailings are neither deposited directly into the deep sea, nor are they placed. The process actually involves pumping mine waste through a short pipe 70-150m in depth, with the mine waste then moving down-slope into the deep sea. The process is also referred to as submarine tailings disposal (STD), but it is accurately defined as Marine Mine Waste Disposal (MMWD).

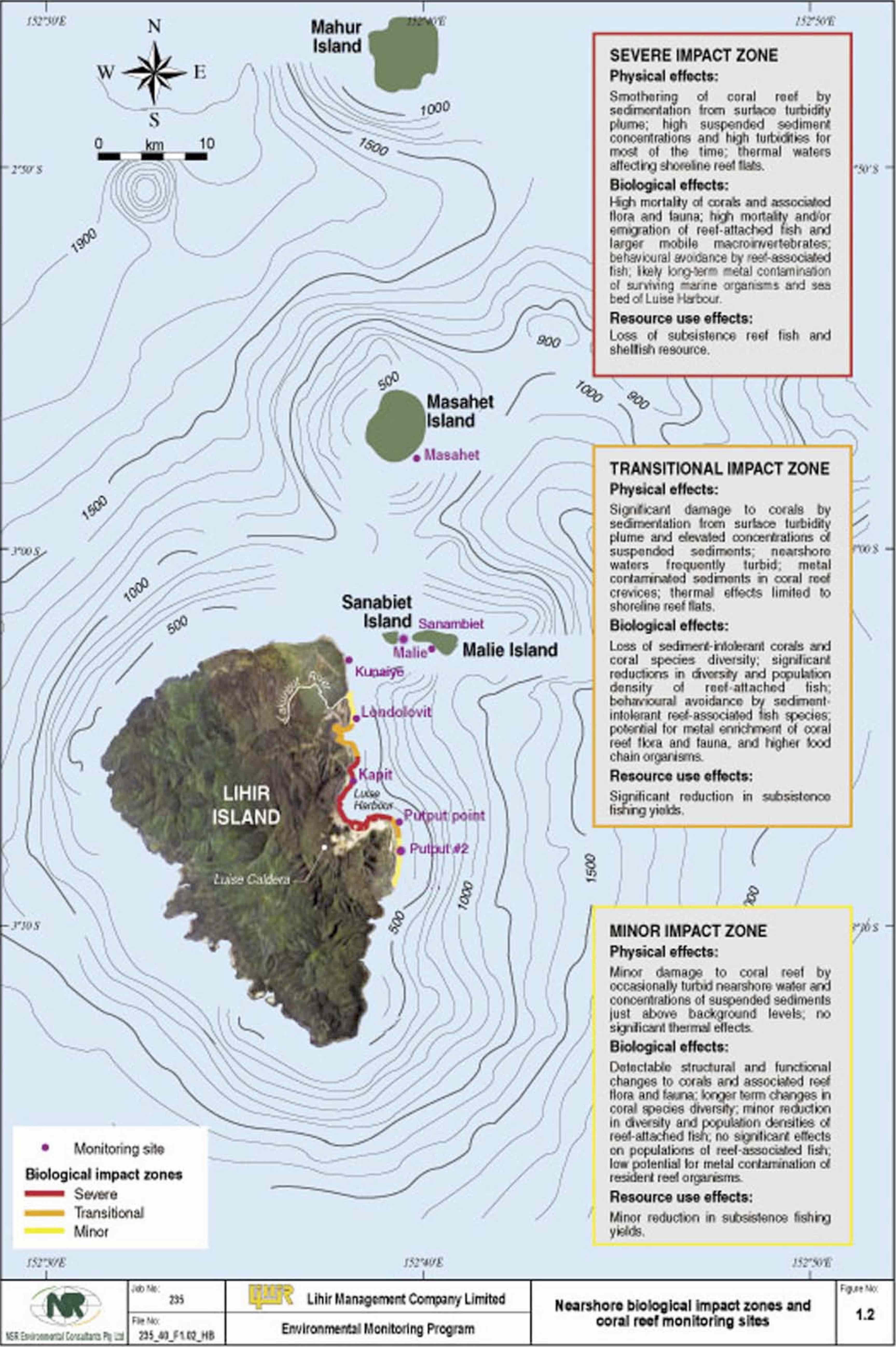

In PNG, the Lihir gold mine discharges approximately 100,000 ML of tailings slurry per year into the Pacific Ocean. This contains an estimated 2.5 Mt of sediment. Over the course of its life, the gold & silver mine on Misima Island discharged approximately 90 Mt tailings into the Solomon Sea. The Simberi gold mine also uses DSTP and the proposed Woodlark Island gold and silver mine is expected to discharge 12.6 Mt of tailings, also into the Solomon Sea.

Ever-increasing waste

In recent years, there have been numerous examples of the very visual environmental impacts of discharging tailings into terrestrial, particularly riverine, environments. The inherent environmental risks of tailings dams and other land-based storage methods make DSTP an attractive and economic disposal option. This is especially true for developing nations that are economically, heavily reliant on exploitation of mineral resources. The need for metals is increasing and, as high-grade ores become rarer, lower grade ores are becoming increasingly exploited. This means that the ratio of waste to metals produced increases. Many lower grade ores, and especially those more difficult to mine, are sulphide mineral ores. These have a very high potential for acid mine drainage and toxic metal contamination. This makes the disposal of tailings one of the most problematic, and contentious issues associated with mining. In PNG and elsewhere, sediments and toxic metals have accumulated in rivers and the near-shore environment, frequently poisoning and degrading food supplies for local inhabitants. This raises the question of whether the environmental impacts of tailings disposal are minimised or avoided by DSTP or is it a case of out of sight out of mind?

Out of sight, out of mind?

The London Convention (1972) and its updated version from 1996, the London Protocol (in place since 2006) on the prevention of marine pollution by waste disposal or other materials, prohibit the disposal of potentially harmful waste at sea. While Australia and other developed nations are signatories to the London Protocol, Papua New Guinea which signed the London Convention, did not sign the London Protocol. Both the United Nations and the World Bank have been critical of DSTP.

Little is known about the environmental impacts of DSTP. In PNG there is very little monitoring carried out. Globally, research on the impact of DSTP has focused on larger fauna found in the open sea and on near shore coral communities. There are some studies which have shown that trace metals (and other classes of contaminants) reduce the richness and evenness of marine communities but next to nothing is known of effects at the deep-sea bed where the millions of tonnes of sediment eventually end up. The geochemical nature of the ore itself dictates how tailings will behave once they are discharged into the environment. Sulphide mineral ores, which when exposed to oxygen either in air or water, will create acids and liberate often harmful metals into the environment and, consequently, the food chain. DSTP requires of access to deep (>1000 m) ocean via a steep continental or island slope. The theory is that sediments will eventually settle deep enough in the ocean where there is little or no oxygen available thereby stopping the chemical reactions that lead to acid mine drainage and heavy metal contamination from taking place. Because the sediment eventually accumulates in the ocean depths, the monitoring of environmental impacts is difficult and expensive. It is hardly surprising then that little is known about the impacts of DSTP.

Known impacts of DSTP in PNG

A recently published, open access study, Ecological impacts of large-scale disposal of mining waste in the deep sea, by David Hughes and colleagues, looked at the effects of DSTP from both Lihir and the former Misima Mine giving us some insight into what actually happens on the ocean floor. The study found that the effects of DSTP at both Lihir and Misima are readily detectable on the seabed.

At Lihir, the operating mine, effects are detectable up to 20 km east of the discharge point and to at least 2000 m water depth. DSTP was considered responsible for greatly reduced abundances and changes in higher-taxon composition of the sediment fauna. The impact on benthic fauna such as metazoan meiofauna and calcareous forams declines with distance from the tailings outfall, but is still significant down to 1700 m. In addition, macrofauna and organic-walled forams (single celled organisms with a calcium or organic shell) are severely impacted to at least 2000 m.

At Misima, three years after mining ceased, abundance of metazoan meiofauna (very small nematode worms and small crustaceans such as ostracods and copepods), macrofauna and benthic forams were markedly different between sites with high and low tailings deposition. Some sites subject to tailings deposition were also characterised by a rarity of peracarid crustaceans (amphipods, isopods and tanaidaceans) which were much more common at sites not subject to tailings.

Although the study was of limited scale and only classified animal abundance classified into very broad groups, it demonstrated that DSTP causes significant changes to the communities of animals investigated. The nature of the impacts of tailings deposition at Misima and Lihir are consistent with published studies from elsewhere that reported substantial loss (or disappearance) of benthic forams, metazoan meiofauna and macrofauna in coastal sediments exposed to mine tailings deposition. Many of the species involved maybe unknown, or even new to science. Their, environmental tolerances, therefore, are also unknown. If an assessment was made looking at the individual species rather than broader classification used, then the impacts would likely be much more profound and readily detectable. While these impacts have been found shortly after deposition, the physical stability of seabed can be compromised for many years. This further extends the duration of impacts and can prevent ecological succession in affected areas of the seabed in an altered, less diverse and biologically unsettled state for many years after tailings deposition has ceased.

The whole premise of MMWD, is based on a severe paucity of data and in comparison with the clearly visible impacts from terrestrial waste disposal methods. The work of Hughes et al. questions this assumption by showing that there are significant impacts from MMWD. Many more detailed studies are required to justify or validate the process as a viable alternative. While no further MMWD should be approved in PNG, it is clear that more monitoring of the seabed is required before, during and after dumping of tailings takes place. The impacts are likely to be no less profound than those already witnessed in the terrestrial environment, just less visible.

By, Dr Simon Judd

Reference

Hughes, D. J, Shimmield, T. M, Black, K. D, and Howe, J. A, (2015) Ecological impacts of large-scale disposal of mining waste in the deep sea. Sci. Rep. 5, 9985; doi: 10.1038/srep09985